In August 2017, an amendment to the Local Authorities Elections Ordinance announced a 25% quota for women in local authorities. However, the drafting of the law undermines its stated intention. The quota for women is designed to fallshort of the promised 25%. This insight explains how far the outcome could fall short of the mandated quota, and what makes it possible.

Local authorities elections in Sri Lanka, after significant delay, are scheduled to take place on 10 February, 2017, under a new electoral system defined by the Local Authorities Elections (Amendment) Act, No. 16 of 2017.

The promise

The Act presents a grand promise. It says in the amended section‘27F. (1) Notwithstanding any provision to the contrary in this Ordinance, not less than twenty five per centum of the total number of members in each local authority shall be women members’ (emphasis added). The underlined words have a very strong implication in law. They suggest that the 25% of women in each local authority is an imperative. The mechanics by which the law is given effect, however, necessarily reneges on that promise.

The mechanics

The gap between the promised quota and the election outcome that can be expected is generated by three factors, which in order of impact are: (1)the exemptions provided to smaller parties, in fulfilling the women’s quota, (2) the relatively low percentage mandated for women nominated for direct elections through the wards, and (3) small anomalies created by rounding-off downwards the number of women mandated by the quota, and in gazetting the women’s quota for each local authority.The precise extent of the gap will depend on the distribution of the votes amongst parties and candidates.

The analysis

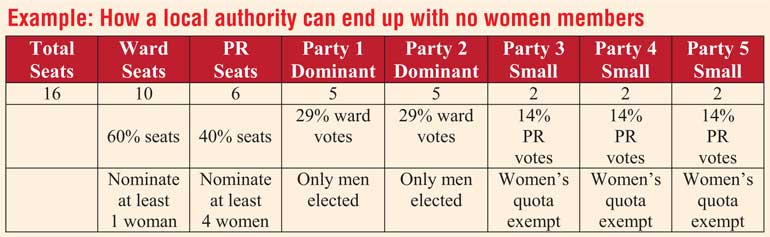

The analysis of the gap presented here is based on a political party and voting distribution scenario that is plausible in the Sri Lankan context. The calculations are based on all local authorities being contested by at least two dominant parties, which together collect at least 50% of the vote; no single party collecting more than 60% of the vote; and there being no more than five parties, inclusive of the two dominant parties, that are able to get at least one seat in the local authority. The outcomes of women being elected can be worse in a scenario which allows for more than five parties succeeding in winning seats, or if a single party could win more than 60% of the vote.

Based on this scenario, Verité Research has the following calculation of the possible gap between the promised 25% and the actual outcome:

- 30% of local authorities can have no women members at all;

- Women’s representation can be 10% or less in more than half of the local authorities

- The total number of women elected to all local authorities can be as low as 15% of the total representation

The anomalies created by rounding-off numbers downwards and in gazetting the minimum quota of women members for each local authority account for a reduction in the total possible representation mandated for women, from 25% to 23.75%. Outcomes that are less than that – and possibly as low as 15% overall – will be due to the exemptions to smaller parties and a limited mandate for ward nominations for women.

The above results are based on the possible (pessimistic) outcome, where the small percentage of women mandated to ward seats, fail to win their seats, and the exemption to smaller parties becomes applicable to their fullest. The actual outcome does not have to reflect these pessimistic possibilities to the fullest, and can therefore be closer to 20% on the whole – while many local authorities could still have no women members at all.

In the example above, the two dominant parties win all the ward seats, while the other three parties each gain less than 20% share of the vote and not more than two seats each through proportional representation (PR). This exempts the smaller parties from having to nominate women off their PR list.

The technicalities

In entering the data for the above analysis, Verité Research counted 341 local authorities. From Gazette numbers 2043/56 and 2043/57, both dated 2 November, 2017, a total of 8,388 seats was calculated. Others provide slightly different numbers which don’t make a material difference to the calculations.

Under the new laws, candidates are elected to each local authority through two lists. The first list has 60% of candidates, who are elected by a plurality of direct votes received by the party at a ward level. The second list is used to top-up the balance 40% of candidates on a calculation of the percentage of votes received from all the wards by each party.

Of the number of members nominated to the wards in each local authority, at least 16.6% will be women (which is the same as one tenth of the total number of seats). Of the 40% of members to be returned through PR, half of the nominees are mandated to be women.

Section 65AA (2) of the Local Authorities Elections Ordinance provides that any party that receives less than 20% of the total number of votes polled in a local authority area, and gains less than three members, is not required to appoint women towards meeting the quota. Innocuous as this exemption may seem, it is responsible for most of the gap that is created between the promise and the outcome. It is also difficult to understand what principle is at stake in allowing for such an exemption.

Verité Research is an interdisciplinary think-tank based in Colombo that provides strategic analysis to high-level decision-makers in economics, law, politics, and media. Comments are welcome. Email:publications@veriteresearch.org. Verité Research would like to thank Chapa Perera of HashtagGeneration for bringing this issue to our attention.

Taken from FT.lk