Taken from – The Washington Post

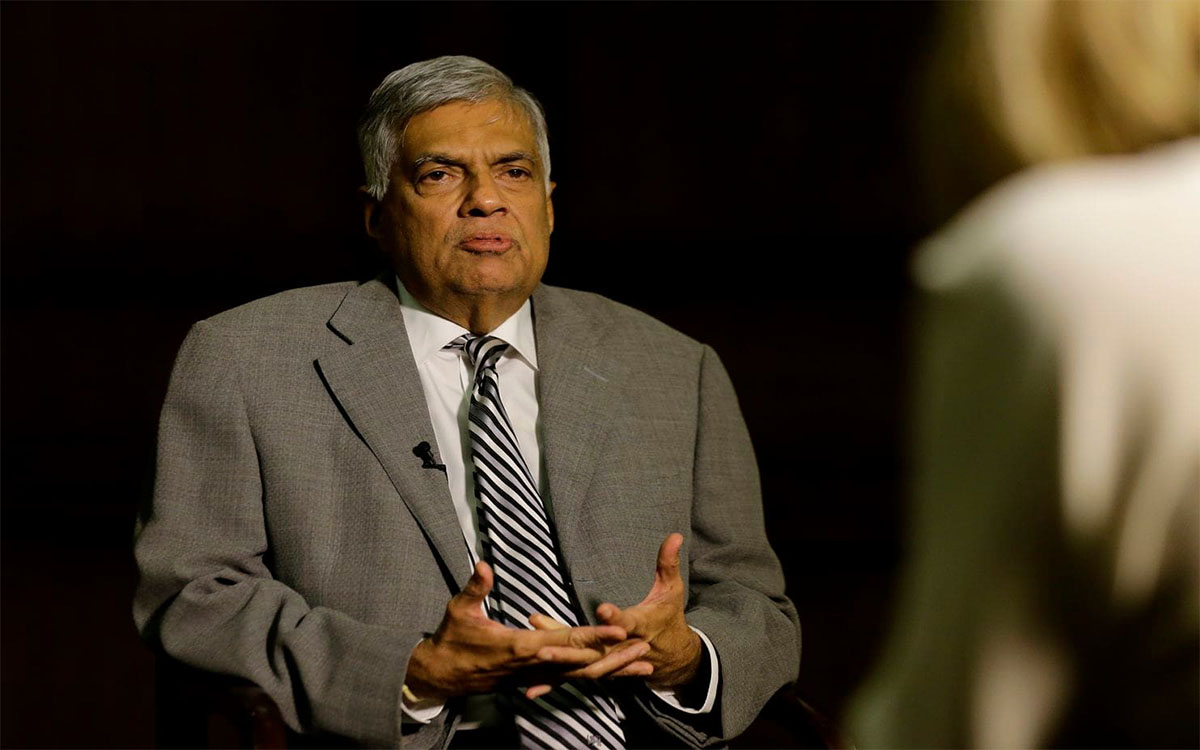

Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe told Sky News on Thursday that the Sri Lankan government had known that Sri Lankan nationals who had joined the Islamic State had returned to the country — but that they couldn’t be arrested, as joining a foreign terrorist organization is not against the law.

His comments came days after attacks on Easter Sunday that killed at least 250. The Islamic State claimed responsibility Tuesday, though the degree of its involvement is as yet unclear.

“We knew they went to Syria. . . . But on our country to go abroad and return or to take part in a foreign armed uprising is not an offense here,” Wickremesinghe said.

“We have no laws which enable us to take into custody people who join foreign terrorist groups. We can take those who are, who belong to terrorist groups operating in Sri Lanka.”

But how could Sri Lanka — a country where a U.S.-government-designated terrorist organization waged war against the state for decades — not have such legislation?

Sri Lanka does have strong anti-terrorism legislation — its Prevention of Terrorism Act of 1978 has in fact been criticized by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. The law allows for “arrests for unspecified ‘unlawful activities’ without warrant, and permits detention for up to 18 months without the authorities producing the suspect before a court pretrial,” as Human Rights Watch put it in a 2018 report. Some say the law allows for targeting and detention of the Tamil minority; the civil war that waged for nearly three decades was fought between the state and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, or Tamil Tigers.

“They have been working on replacement legislation called the Counter-Terrorism Act, which is designed to be a) more rights-friendly and b) more responsive to current forms of threat, but the law remains in drafting stage, after numerous rounds of deliberations in government and parliament,” Sri Lanka analyst Alan Keenan of the International Crisis Group wrote in an email.

Some could argue that the prime minister is making as much a political case as a legal one — the Sri Lankan government did fail to stop deadly terrorist attacks. And the government does have the power to issue regulations that make it an offense to be a member of a terrorist organization outside Sri Lanka, explained Gehan Gunatilleke, former United Nations advisor to the Sri Lankan foreign ministry and current graduate law student at Oxford.

In 2011, the government made it a crime to be a Tamil Tiger even outside of Sri Lanka. “These regulations contain a broad range of offences including a provision that says ‘no person shall within or outside Sri Lanka…be a member of the LTTE,’” Gunatilleke wrote. “So under the current law, the minister has the power to proscribe any organisation, and make membership of that organisation both within and outside Sri Lanka an offence.”

Nevertheless, the preexisting anti-terrorism law in Sri Lanka was obviously written in, and for, a different time. It’s hardly unique in that.

Many countries amended their relevant legislation after 2014, the year that the Islamic State declared itself a caliphate. In 2014, Australia passed its Counter-Terrorism Legislation Amendment (Foreign Fighters) Bill, which made new offenses of “advocating terrorism” and “of entering or remaining in a ‘declared area’ of a foreign country in which a terrorist organization is engaging in hostile activity.” That same year, Ireland proposed a Criminal Justice (Terrorist Offenses) (Amendment) Act, which made it an offense to, among other things, recruit and train for terrorism (the bill is now law).

“Even for countries that have criminalized membership in foreign militant groups or other terror offenses abroad, it can be difficult to collect enough useful evidence from a foreign battlefield to meet a prosecutorial standard,” Sam Heller, senior analyst of nonstate armed groups at Crisis Group, wrote in an email. “That’s why countries like Australia have passed ‘declared areas’ legislation, which prohibit their nationals from visiting specific countries or areas such as Raqqa. So it’s not so easy — I think everyone’s trying to figure it out.”

And Sri Lanka isn’t alone in not having legislation that makes it illegal to join a foreign terrorist organization. The issue has been recently debated in Sweden. Last month, the Swedish government moved ahead with a proposal for legislation that would make it illegal to participate in or cooperate with a terrorist organization. But the proposed legislation suffered a setback when the Council on Legislation suggested it is incompatible with Sweden’s constitutionally protected freedom of assembly. And so now local, state, and social services are working together to determine whether individuals have committed war crimes, because, under current Swedish law, a specific crime needs to be suspected before an investigation can be opened, a resource-intensive process.

“Strained resources is part of why some countries are reluctant to have their foreign fighters return home,” Heller wrote.